Talk by Zsuzsa Berecz & Árpád Bőczén at Interpret Europe Conference 2023

This year’s Interpert Europe Conference was organised under the motto: Creating learning landscapes through heritage interpretation. Several members and collaborators of KÖME participated at the conference in Sighișoara between 11 and 16 May, 2023.

In a series of posts we give you an insight into our experiences and contributions during the Interpret Europe Conference 2023 in Sighișoara.

At the conference Zsuzsa Berecz and Árpád Bőczén gave a talk about the topic HERITAGE IN MY BACKYARD, focusing on the concrete example of the small private Iron Curtain Museum on the Austria-Hungary border.

In the presentation Zsuzsi and Árpád walked the audience through the challenges they faced at the first phase of planning and creating a sustainable and (more) interpretive learning environment at this small private heritage site. They discussed how ownership, participation and co-creation surfaced throughout their work and what they learned from them so far.

Here you can read a shortened and edited transcript of the talk.

Árpád Bőczén.: You are a dramaturge, right? How does a dramaturge come into contact with heritage, especially with such we saw in the video?

Zsuzsa Berecz.: I am very much interested in the micropolitics of everyday life and what I would call the microdramaturgies of the ordinary. To me heritage is part of the contexts we are living and actin in. I find it interesting how preserving history can become a necessity, a personal need, and what personal and collective rituals we create in order to preserve heritage.

In this picture for example you see Aunt Vilma gardening right next to the barbed wire of the Iron Curtain. Their fields were bordering to the so called “System” on the Austria-Hungary border and she could see the barbed wire at work each day.

Iron Curtain is not only a historical term or heritage but it was actually part of everyday life to many people.

I came into contact with the Iron Curtain Museum in 2018 when we prepared the Interpret Europe Conference in Kőszeg. As part of the conference we organised study trips and in this framework we started researching the heritage of the Iron Curtain.

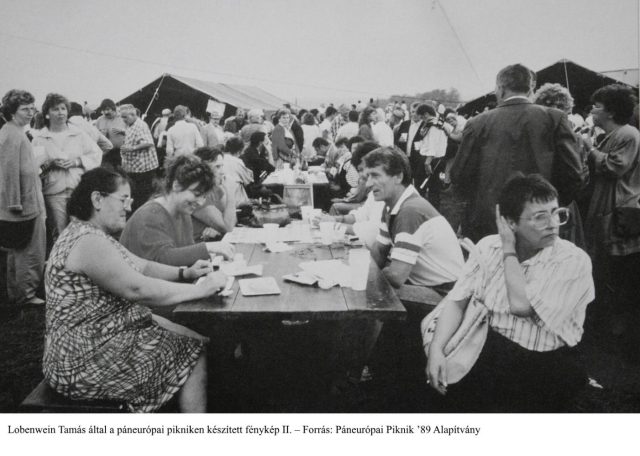

We visited among others the Pan European Picnic site near Sopron, the small Burgenländisches Geschichte(n)haus / House of Burgenland Histories with an Iron Curtain Experience Trail and we also visited the Iron Curtain Museum in Felsőcsatár.

I became intrigued by the civil courage I witnessed on this border area, I liked the way people felt the need to inherit what happened in this border zone before 1989. For example the Pan European Picnic was initiated and organised mainly by private people to make a gesture that the Iron Curtain has become obsolete, although later on several political players reclaimed this heritage (as you can see today at the Pan European Picnic site which is loaded of symbols and memorials erected by various parties). When observing these chains of inheritance versus big historical narratives I became very much intrigued by the clashes of those. I started to look into what role so called ordinary people play in the creation of history and its interpretation.

Á.B.: You say dramaturgies of the ordinary, I say ordinary connections which are more colorful in ordinary situations compared to institutionalized heritage in my experience. The first exists because of these ordinary connections while in case of the second these ordinary connections need to be established mostly. If we think about ordinary connections, these are often not even conscious, people don’t think of them as heritage, they live in it and with it.

The next question arises here. Many times this kind of heritage is hard to grasp. What is the heritage in the case of the Iron Curtain Museum and what creates the necessity for it to emerge?

ZS.B.: The heritage is manifold here. Founder Sándor Goják was not motivated by a historical curiosity in the first place. His motivation for this heritage came via tourism and gastronomy. He was a conscript border guard on the AT-HU border in the 1960s and afterwards he settled down here. After the Fall of the Wall the family opened a pub on the Iron Hill. In this pub their guests were mainly tourists who came here to experience a place which was a no man’s land till 1990 or to commemorate their own escape or the escape of some family members. The village Felsőcsatár is right at the border and the Iron Hill was in-between the border zone and the technical barrier (the so called “System”). Only people who had property up there could go up to the hill and even they had to leave the hill before dusk. After 1989 there was a growing interest in places like this.

Sándor is a big storyteller and he started telling stories to his guests. His stories became complemented by those of others who came to his pub or who he accidentally met and also those who he purposefully interviewed, because his engagement grew. After a while he started actively researching himself and traveled hundreds of kilometers to meet witnesses of those times. In the end of the day these became all “his stories”, he filtered them.

First he performed in the pub as storyteller and after some years he started building up an open air museum in his vineyard behind the pub. Then this museum became his stage where he performed as a storyteller. The whole infrastructure of the museum is set up to be “handy” for Sándor as a performer. This is Sándor’s ritual of preserving and sharing heritage. So to answer your question: here the heritage is a complex one because it is of course the Iron Curtain, the collection with its objects, stories, with its location and the person of Sándor Goják.

Á.B.: But what is missing or what could be developed if the heritage is so live and the presentation is so strong and personal already?

ZS.B.: The Iron Curtain Museum is extremely fragile. Take out Sándor’s person and the place becomes fragmentary, chaotic or even mute, endangered. He is getting old and each time I visited him he kept saying that he wanted to inherit the collection. He thought about the Hungarian state; he even made steps to draw Hungarian decision makers’ attention to the collection, but without success. Then the Stasi Museum from Berlin wanted to acquire some objects but he decided to keep them together there.

What happens to the museum if the physical presence of Sandor is not given? This was our initial question. Our point of departure was to enrich the interpretation which was so far exclusively organised around Sándor’s person as storyteller. Our idea was enrich this interpretation by other voices and perspectives.

In the Muse.ar project we worked with artists and creators Claudio Beorchia and Mátyás Kálmán. Their idea was to take Sándor’s stories as basis and to add other points of view to the narratives. The creators imagined what the different people involved in the given story could have thought. Claudio Beorchia wrote short monologues with those speculative thoughts. Those monologues or small epitaphs then were audionarrated and merged into an audio walk.

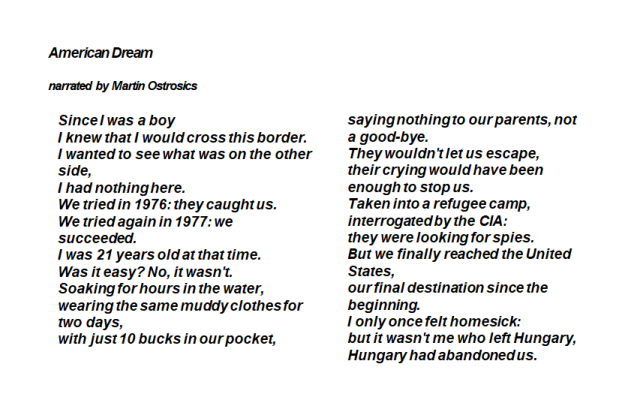

This was a nice process of co-creation, as the museum’s manager, Sándor’s daughter Anett chose people from their network, from the village or nearby villages and towns to narrate these monologues in Hungarian and German. It was nice that Anett also became part of the creation. There were nice moments here: for example a person (Martin Ostrosics) who escaped from here and emigrated to the USA tells his own story Claudio wrote based on an interview with him.

Á.B.: You mentioned co-creation as a principle in this new content development. What did it exactly mean? How was such a way of creation possible if the involvement of the personality in the original presentation is so strong andif the interpretation is so much connected to Sándor?

ZS.B.: The co-creation was not a linear process, it was a constant negotiation with Sándor and with the other people involved. Parallely to this creation process we started to work with his daughter Anett. She got more and more engaged and after a while Sándor started calling her the boss of the museum. Anett took over more and more management tasks and she got involved also into the creation process. At the same time when it comes to concrete changes within the museum it is still Sándor who has the last word, so there is a lot of negotiation involved.

Á.B.: What did Sándor contribute to the new development?

ZS.B.: Primarily: he told us his stories. This was when we realised that he tells these stories almost in the exact same way all the time. He developed this ritual of telling the stories and it’s almost impossible for him now to tell them differently. At the same time by talking to him we managed to tackle out new stories from him, incl. some he kind of hid before (for example his story of stealing coal from the military for a comrade of his, who lived nearby among very poor circumstances. This is a story he hid before because he committed a crime here which he is of course not proud of).

So during the creation process Claudio wrote the monologues and for some time we only had the monologues as audio material. Then Sándor listened to them and was not happy: he said they have a lot of flaws, the stories are not complete. After a while it became obvious that Sándor’s narration is a necessary part of these stories. So finally the audio walk contains Sándor’s intros to each story and then the monologues revealing the stories from different perspectives.

Á.B.: Ok. It seems that the cooperation with Sándor was crucial in this project but what was the perspective of the other actors, the artists and the interpreters? Was it really necessary to involve both fields, interpretation and art? How could we distinguish between the two approaches?

ZS.B.: The project Muse.ar was an experiment to strengthen new kinds of collaborations between people working in different fields. The project involved 3 different heritage sites where interpretation was on different levels, with different institutional backgrounds and we tried to bring the existing interpretation into a dialogue with artistic approaches, using digital technologies. This was a big challenge to all participants because it was about finding new ways of collaboration beyond the usual model where an institution commissions artists and/or IT developers to realise something that was conceived by the museum.

What we tried in this project is to create a common ground for all the teams working on the 3 sites. This common ground of framework was the interpretive approach.

When preparing for this talk I asked artist Claudio Beorchia who worked with us at the Iron Curtain Museum what difference it made for him to work with this interpretive framework.

“I would say that the big difference between this project and the art projects I generally do is the collegial system by which it is conceived and developed. Generally, in all my projects, even the more relational and participatory ones, I have more autonomy in the conception and configuration of the project. Generally, what guides me in this configuration process is essentially the desire to achieve the greatest aesthetic quality, understood as poetic valence and depth of meaning.

In the Hungarian case, on the other hand, the working group was more and differently structured, and different aspects were also taken into account, which I generally do not take into account, such as “target audience,” the technological framework of the app, and the explicit requirements of the museum.”

He described his approach and its relation to heritage interpretation like this:

So this shows that interpretative approach could be considered a square frame for artists. In my understanding this looks different. I work both on the art field and also on the heritage field. For me the interpretive approach is basically about looking at the whole context of what I’m doing as a curator: who are the stakeholders involved, what are their motivations, who will we make an artwork for, what are the political, ecological etc. circumstances. In my understanding it is, if you wish a more organic, more flexible approach because it keeps an eye on these different factors. So I could even turn this image around and say that using an interpretive approach as I understand it is more like an amoeba compared to just getting inspiration from the context for an artwork as an autonomous entity. I think this approach is also more in the favour of sustainability as it considers the different motivations, different relationships and connections in-between people and other entities and the heritage itself.

Á.B.: Why do you think that the development you realized with this app is sustainable and that it contributes significantly to an (more) interpretive learning environment?

ZS.B.: Sándor’s person is key also for the sustainability of this audio walk app as well, at least for the near future. Will sándor use it and suggest it to the visitors or not? We’ll see. I think it is key in such a situation that the people of the heritage site like the artwork. The more they are engaged with it or even involved in the creation, the more likely it is that they will like it.

For us an important step towards sustainability was to grant access to other people than Sándor to this heritage. So far the only contact point was Sándor: he was the performer and other than that there were only spectators so to say. We thought that by moving others into the position of creators and stakeholders we could make a big leap towards sustainability after Sándor’s passing.

Dramaturgically speaking: the app we developed introduces other voices and offers other contact points and thus entry points into this whole heritage. It gives a wider perspective on sándor’s interpretation. if you wish, some kind of interpretation of an interpretation, framing of a framing. The way Sándor frames history becomes visible here. He doesn’t reflect this otherwise and that might be problematic from a museological point of view. Now I think we succeeded in showing how he is part of this heritage as a storyteller.

Also, such a piece of work opens up a possibility for later additions, for new voices, agencies for the site, for the stories. By opening up and diversifying the stories we paved the way for opening up the site for other agencies. By this we addressed Sándor’s contradictory attitude: that at the same time he wishes for new people to enter and help him but at the same time he makes the place rather exclusive. Ownership is a key factor in sustainability, and opening up ownership.

I’m wondering, from your point of view as heritage manager who is the owner of a heritage like Sándor’s? We talked about co-creation but can we talk about co-ownership in this case?

Á.B: The ownership is very sensitive in such cases. The tension comes basically from the duality that the objects, the property belong to Sándor and to his family but the social value of the whole can’t flourish without the deep engagement of others as well. When it comes to the role of interpretation we are trying to experiment with the approach and use it to generate connections, to build up strategies for the museum and to establish a more systematic management. So interpretation and management go hand in hand. We are lucky that Sándor wishes to pass on the whole collection to some entity which can ensure its future. However we don’t know yet what the heirs will do with the museum property and the materials there.

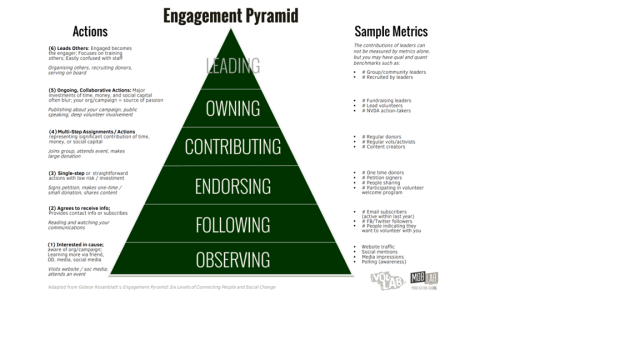

On the other hand ownership is a higher level of engagement. Mapping engagement.

Engagement Pyramid By Gideon Rosenblatt, Former Groundwire Executive Director

Zs. B: In such cases who is in the position of granting access to others to higher levels of engagement? And who decides about who these “others” are?

Á.B.: At this moment this entity is Sandor himself. But it is obvious that he isn’t conscious in this sense. He feels responsible to bring together ex border guards and he likes that the collection is visited by foreign tourists from many countries and continents, but it is a fact that the locals don’t visit the place. We don’t know the reasons yet (there can be many) but it is definitely one issue from the many which need attention.

We decided in 2018, that we give a try to help him and his relatives to become more conscious about the future possibilities of this museum. We don’t want to make decisions but to help them to make them and to collect and engage those who can be the owners and managers. At the moment the museum doesn’t exist legally. It is just a private winyard of a person. The first step is to put it on different maps. Touristic maps, Maps of Collections, Professional maps, and of course the mental maps of all the stakeholders. This work requires us to play different roles like mediators, curators, mentors, managers, just to mention some of them. The results of the first year, just ti list them: an inventory of the collection was made; we made a SWOT analysis, a needs analysis and a stakeholder map. Also the MUSE.ar development was a crucial achievement.